Een verslag van Mali Muso over de situatie in MaliTrouble in Timbuctu – my memories of Mali

by mali muso

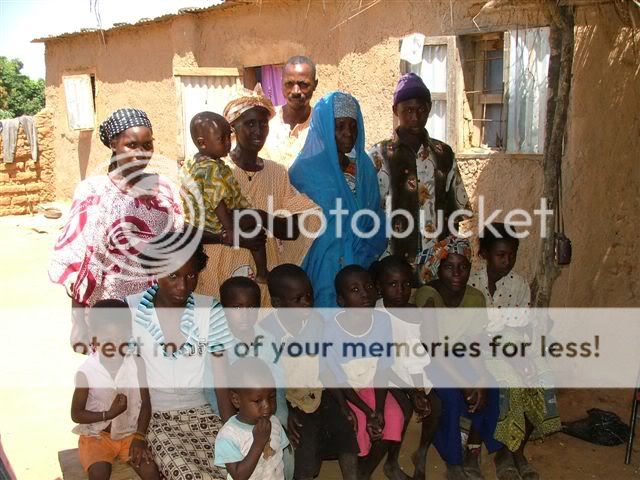

When I received my invitation to join the Peace Corps in Mali in 2003, little did I know that my time in this corner of West Africa would change my life profoundly. My work with my Malian government colleagues in the tourism and handcraft development sector taught me not only about the incredibly rich history and culture of this great nation but also important lessons on the values of friendship, community and dialogue. I even found romance and my life partner. So my connections to this land and my interest in the recent events that have only just now started to pierce the consciousness of the mainstream media are quite deep.

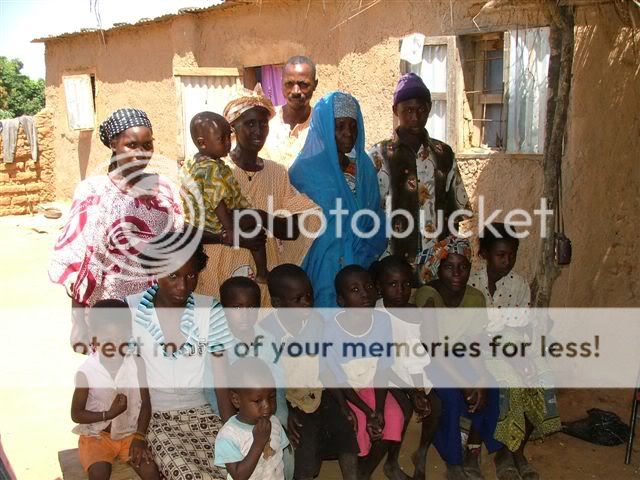

I have never diaried at DKos before, but as the events in Mali began to take dramatic turns, I thought it might be worthwhile to share some of my own perspectives, reflections and analysis to bring a bit more detail to a news story that is probably pretty opaque and foreign for most. Please keep in mind that I’m not a historian, political scientist or journalist. I’ve done my best to do justice to the story, having read hundreds of news articles, tweets, and blogs, but I’m no expert. I may gloss over details or use shorthand that makes sense to me because of my closeness to the situation, so please feel free to call me out in the comments and engage in dialogue. All photos are mine. With that disclaimer, here goes:

A brief history

Any young child in Mali can recount for you the stories of Sundiata Keita, Mansa Moussa and many of the other legendary names of Malian past. The history of Mali is rich and proud, the location of the great empires of Mali, Ghana and Songhai. The peoples and ethnic groups that made up these empires still inhabit the area today, albeit sometimes spilling over into various neighboring countries due to borders drawn up by the French colonial powers.

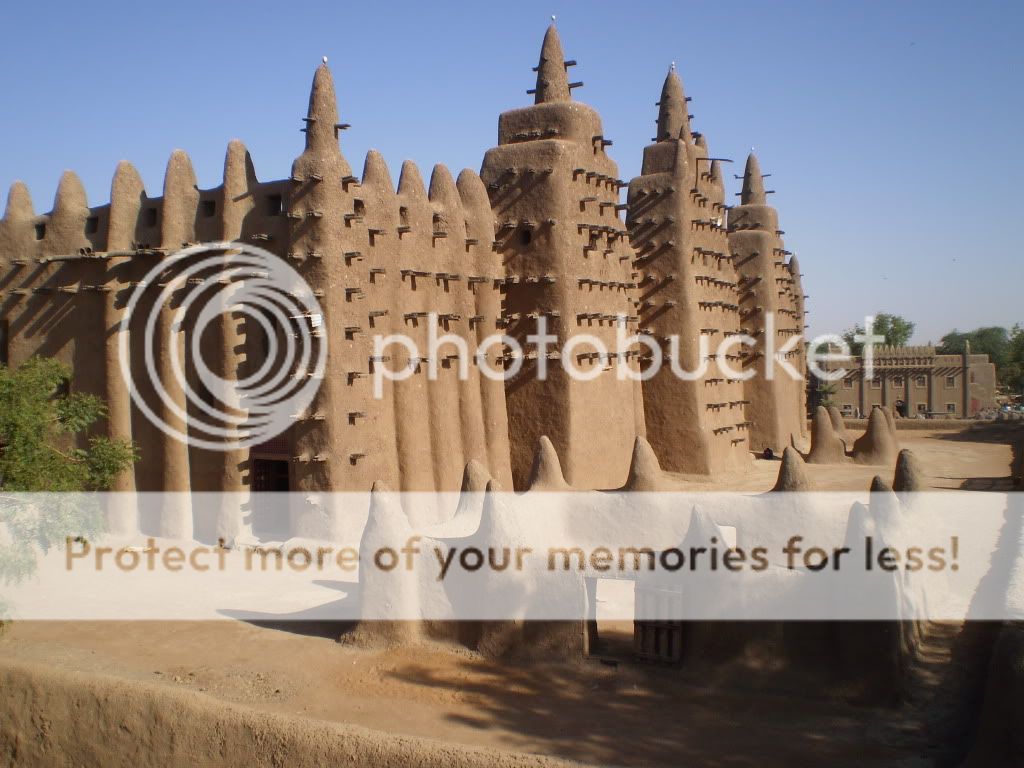

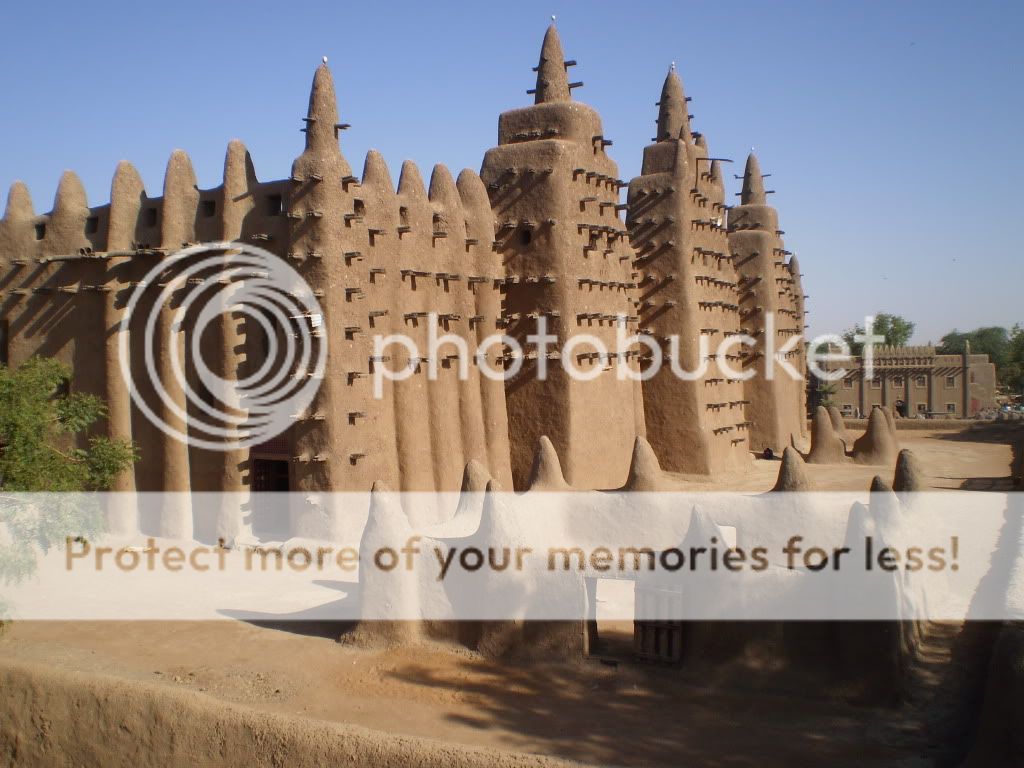

One of the cities that was part of the Empire of Mali is the legendary Timbuktu, the mysterious city which has intrigued the outside world for centuries. Located at a strategic point intersecting trade routes from the Sahara and the Niger River, it grew from a small settlement into a center for commerce and education. One famous story recounts that when king Mansa Musa went on his pilgrimage to Mecca, he carried with him such wealth and spread around so much gold that it created inflation and destroyed the economy in Egypt and Saudi Arabia for the next decade. Upon his return, he built universities and mosques in Timbuktu and Djenne and the area became known for its Islamic scholarship as well as trade.

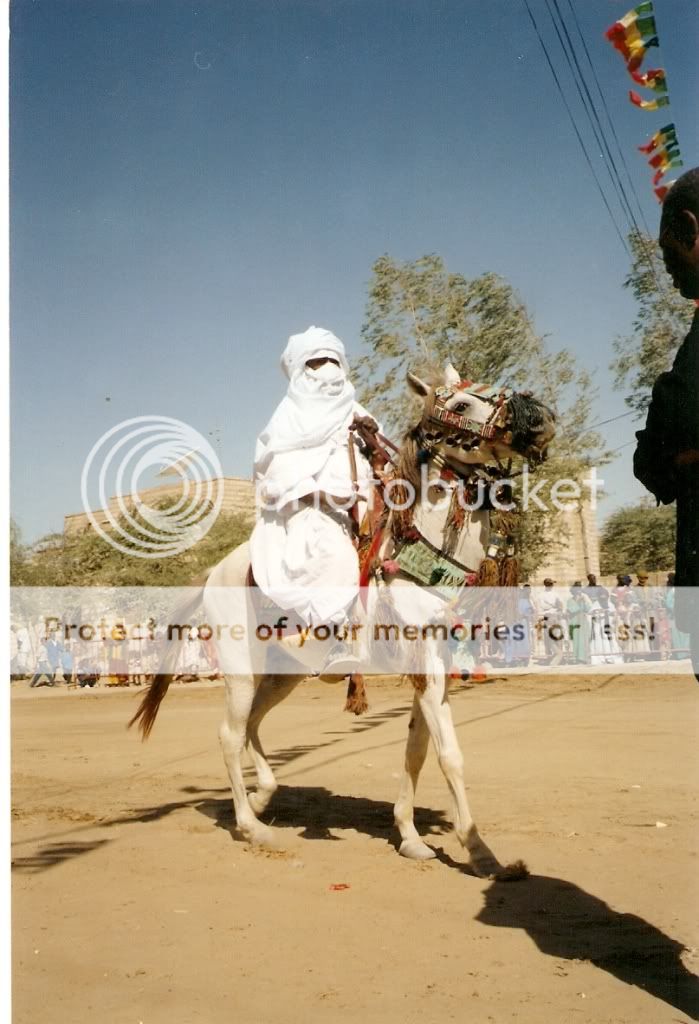

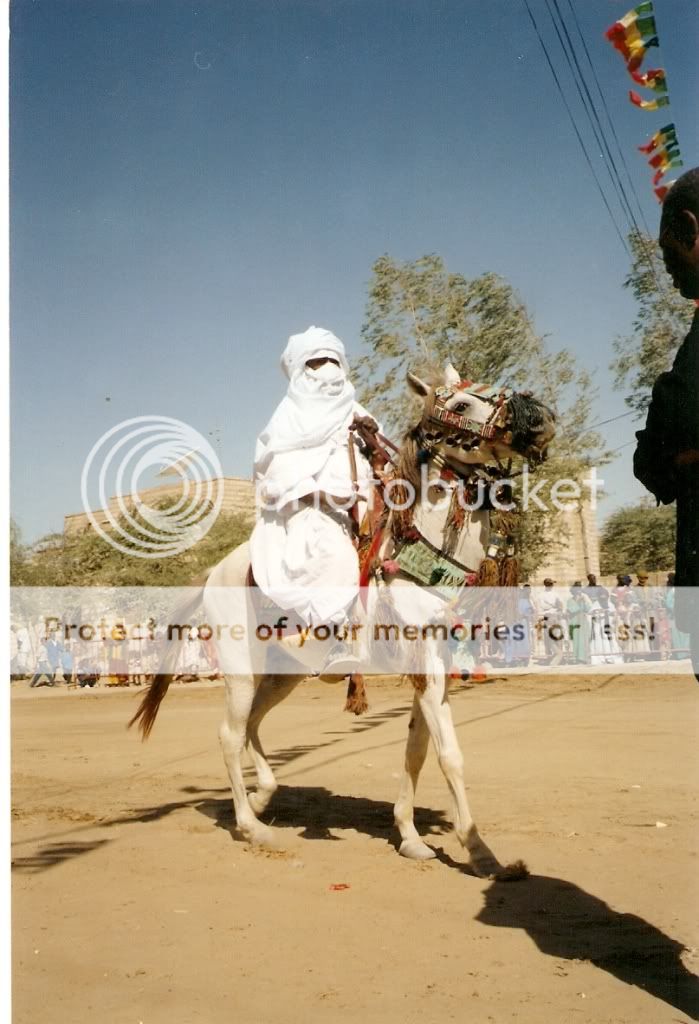

My own memories of Timbuktu are of quiet, dusty streets and cool, dark rooms protecting their inhabitants from the fiery midday sun. Visiting some of the collections of the ancient manuscripts, poring over the elegant Arabic script, drawings and mathematical notations. Sharing sweet strong shots of tea with a Tuareg artisan while we sat in his courtyard and watched him create magic from leather. The feel of fine grains of sand between my toes as we stood on a dune in the Sahara, looking out across the sea of sand and hearing the wind whistle around us. Buying fresh, hot flatbread made in outdoor clay ovens by Songhai women.

The Tuareg in Mali

Mali and much of the rest of West Africa was later colonized by the French. Independence was not gained until 1960. One of the legacies of French colonialism was the inclusion of the Tuaregs of the south Sahara in the modern nation-state of Mali. Although there was consideration of splitting part of the northern territory away as a separate state, it was quickly realized that any northern state would need to include the Niger River in order to have a viable economy. The land around the Niger (including the cities of Timbuktu and Gao) was populated by a variety of ethnic groups such as the Songhai, Fulani, Bozo, with the Tuareg a distinct minority. These groups see themselves as Malian and would not have been amenable to being forced to separate and live in a Tuareg state.

There has been tension ever since with Tuaregs wanting more autonomy and independence in the north, and Mali seeking to keep their territory intact. How one sees this tension depends very much on which side you come from. Southern Malians will say that they’ve given the Tuareg special consideration in terms of being promoted in the military ranks and having slots reserved in civil society jobs. Tuaregs will say that the part of the country where they live is neglected in terms of development (economic, medical, cultural, etc.) and that they want to be better represented in making decisions about the issues that affect them.Another factor that you won’t see mentioned in the news reports but which I have seen personally (on both sides) is that of race. Southern Malians would say that the Tuareg (who are related to the Berber of North Africa) think they’re better than them by virtue of their lighter skin. I know that when I lived there I was told several times by Tuaregs that they were like me, eg. white and that “we” were not like those “black people”. Sadly, the misunderstandings and stereotypes go both ways and are part of the undercurrents playing a part in where things stand today.

Mutiny in the capital and rebellion in the north

After the fall of Ghaddafi, a mass of Tuareg fighters migrated back to the Sahara region of Mali armed with weapons and ammunition. They rekindled the rebellion and are well-organized and well-armed. When they began attacking small settlements in the far north, the Malian army found itself under-equipped and outgunned. The Malian army suffered many defeats, and the President Amadou Toumani Toure (ATT) was accused of being “too soft” on the rebellion and of not giving the army the resources they need (food, manpower, ammunition).

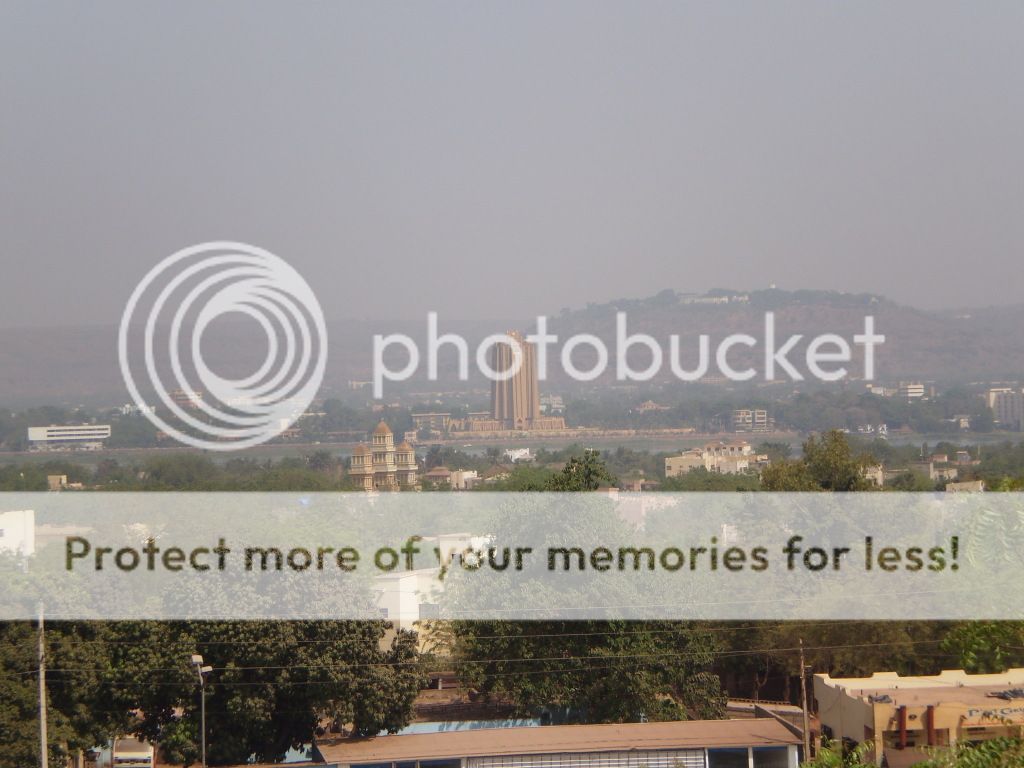

On March 21, a visit from the defense minister to the troops garrisoned outside the capital of Bamako turned into a confrontation with angry soldiers protesting what they saw as incompetent leadership. This escalated into a mutiny and the soldiers stormed the presidential palace as well as the offices of the national television station. This junta of mid-level officers led by Captain Sanogo suspended the Constitution, saying that they would return the government to a democratically elected transition. Ironically, elections were due to be held in less than a month, and President ATT had made clear his intentions to step down and retire.

In the midst of this confusion in the capital, Tuareg rebel groups in the north took advantage to consolidate their positions and advance to capture more territory. Within three days time, they had captured the regional capitals of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu and declared that they were “liberating” the country of Azawad.There are at least three distinct groups involved in the fighting as well as opportunistic criminal and bandit elements. Here is a brief (and overly simplistic) rundown. The MNLA is a collection of liberation-minded Tuareg groups who are seeking independence or at least more autonomy from Mali. Ansar Dine is another group whose goal is not Tuareg independence but the imposition of Islamic law in Mali. Finally, there is AQIM or Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb which is associated with factions in Algeria and who make money from drug trafficking across the hostile desert terrain and kidnapping hostages for ransom. Reports indicate that the takeovers of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu have been achieved by some or all of these groups working together. What remains to be seen is whether or not they will turn on one another now that their territorial objectives have been achieved. Reports from Timbuktu and Gao seem to indicate that in fact the Islamist elements have the upper hand.

In the meantime, ECOWAS (the economic community of West African states) held emergency meetings to respond to the coup. ECOWAS took a very hard line with the junta, no tolerance for coups. They gave them 72 hours to return the country to constitutional rule. Sanogo announced a return to the original constitution (he and his mutineers had hastily drawn up a new constitution in the span of about a day), but refused to step down or to agree to a timeline for transition. ECOWAS instituted an embargo, closing the borders with Mali and freezing their ability to draw on the common West African currency, the CFA. Within the span of a few days, a deal was negotiated in which in which the speaker of Mali’s National Assembly, Dioncounda Traore, was sworn in as interim president. He has 40 days to organize elections. The most pressing issue is resolving the crisis in the north.Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world. The land in which most of the population lives is increasingly affected by desertification and the effects of global climate change. Already this year was forecast to be a bad one in terms of drought and food insecurity. The precarious security situation in the north has displaced thousands already and more will likely follow.

The Mosaic of Mali

Almost all of the major ethnic groups in Mali have had their heros and their time of ascendancy. Bambara, Songhai, Soninke, Fulani, Mande, each can point to a time in the history and cite how their ancestors were great and made a real contribution to the shared patrimony of Mali. There is a fascinating practice that goes on to this day called “le cousinage” or “sanankuya” which in English is roughly translated as “joking cousins”. During my Peace Corps training, this was one of the first bits of culture that we learned and started to practice along with our budding language skills. Essentially each last name, ethnic group and/or caste is related to certain others as “joking cousins.” When you meet someone, perhaps sit beside them on the bus, buy something from them in the market, etc. one of the first questions asked will be “what’s your family name”. If it turns out that you and your interlocutor are joking cousins, you immediately begin trading good-natured insults and jokes. You’re no longer strangers; the ice is broken. We were told by our Malian trainers that they credited the long history of peace and diversity to this practice. By disarming potential rivalries through humor and giving a social outlet for acknowledging shared cultural history, serious fighting or feuds could be avoided.There are infinitely more small quirks like this this that one could share to demonstrate the Malian propensity towards dialogue, tolerance and optimism. I could tell you about the amazing musicians, known around the world for their artistry, talent, and ability to synthesize musical traditions across ethnic lines, or about the griots, oral historians who to this day can recount the entire histories of the clans to which they are traditionally linked, or the culturally ingrained practice of using mediators to smooth over disagreements in the community, or the traditional greetings and blessings that complete strangers exchange every day, or the way that passerbys are invited to share meals. I wish I could find the words to show clearly the Mali that I know and love and the degree to which this recent violence is so contrary to the norm.

The Malian people are generous and community minded. From the empire of Mali thousands of years ago to today, their culture and identity has remained intact. One can only hope that the values of dialogue and jiatigiya (hospitality) will see them through these dark days.

I hope that this diary has given at least a small glimpse at a situation that affects a country that is near and dear to my heart. I would be happy to take a stab at any questions or engage in discussion with anyone who is interested or curious.

For further reading, I’d recommend the following:

Bridges from Bamako – an excellent blog that has great analysis before and throughout the coup

Disaster looms for people of Mali as country is split by revolt

Hungry for Democracy – The Malian peasantry and the coup

The coup in Mali is only the beginning

Musical reflections on dramatic events in Northern Mali

Finally, I leave you with one of Mali’s most famous exports, music. Here we have artists from many of the major ethnic groups (including Tuareg) united in song and in celebration of their shared culture.

I can’t hit submit without forgetting to thank everyone at Black Kos for being so supportive, Denise Oliver Velez for encouraging me to take a stab at diarying this story, nomandates for getting me plugged into the New Diarists help network, and bent liberal for LOTS of editorial advice and patience. Aw ni ce, aw ni baara ji. Thank you!!

When I received my invitation to join the Peace Corps in Mali in 2003, little did I know that my time in this corner of West Africa would change my life profoundly. My work with my Malian government colleagues in the tourism and handcraft development sector taught me not only about the incredibly rich history and culture of this great nation but also important lessons on the values of friendship, community and dialogue. I even found romance and my life partner. So my connections to this land and my interest in the recent events that have only just now started to pierce the consciousness of the mainstream media are quite deep.

I have never diaried at DKos before, but as the events in Mali began to take dramatic turns, I thought it might be worthwhile to share some of my own perspectives, reflections and analysis to bring a bit more detail to a news story that is probably pretty opaque and foreign for most. Please keep in mind that I’m not a historian, political scientist or journalist. I’ve done my best to do justice to the story, having read hundreds of news articles, tweets, and blogs, but I’m no expert. I may gloss over details or use shorthand that makes sense to me because of my closeness to the situation, so please feel free to call me out in the comments and engage in dialogue. All photos are mine. With that disclaimer, here goes:

A brief history

Any young child in Mali can recount for you the stories of Sundiata Keita, Mansa Moussa and many of the other legendary names of Malian past. The history of Mali is rich and proud, the location of the great empires of Mali, Ghana and Songhai. The peoples and ethnic groups that made up these empires still inhabit the area today, albeit sometimes spilling over into various neighboring countries due to borders drawn up by the French colonial powers.

One of the cities that was part of the Empire of Mali is the legendary Timbuktu, the mysterious city which has intrigued the outside world for centuries. Located at a strategic point intersecting trade routes from the Sahara and the Niger River, it grew from a small settlement into a center for commerce and education. One famous story recounts that when king Mansa Musa went on his pilgrimage to Mecca, he carried with him such wealth and spread around so much gold that it created inflation and destroyed the economy in Egypt and Saudi Arabia for the next decade. Upon his return, he built universities and mosques in Timbuktu and Djenne and the area became known for its Islamic scholarship as well as trade.

My own memories of Timbuktu are of quiet, dusty streets and cool, dark rooms protecting their inhabitants from the fiery midday sun. Visiting some of the collections of the ancient manuscripts, poring over the elegant Arabic script, drawings and mathematical notations. Sharing sweet strong shots of tea with a Tuareg artisan while we sat in his courtyard and watched him create magic from leather. The feel of fine grains of sand between my toes as we stood on a dune in the Sahara, looking out across the sea of sand and hearing the wind whistle around us. Buying fresh, hot flatbread made in outdoor clay ovens by Songhai women.

The Tuareg in Mali

Mali and much of the rest of West Africa was later colonized by the French. Independence was not gained until 1960. One of the legacies of French colonialism was the inclusion of the Tuaregs of the south Sahara in the modern nation-state of Mali. Although there was consideration of splitting part of the northern territory away as a separate state, it was quickly realized that any northern state would need to include the Niger River in order to have a viable economy. The land around the Niger (including the cities of Timbuktu and Gao) was populated by a variety of ethnic groups such as the Songhai, Fulani, Bozo, with the Tuareg a distinct minority. These groups see themselves as Malian and would not have been amenable to being forced to separate and live in a Tuareg state.

There has been tension ever since with Tuaregs wanting more autonomy and independence in the north, and Mali seeking to keep their territory intact. How one sees this tension depends very much on which side you come from. Southern Malians will say that they’ve given the Tuareg special consideration in terms of being promoted in the military ranks and having slots reserved in civil society jobs. Tuaregs will say that the part of the country where they live is neglected in terms of development (economic, medical, cultural, etc.) and that they want to be better represented in making decisions about the issues that affect them.Another factor that you won’t see mentioned in the news reports but which I have seen personally (on both sides) is that of race. Southern Malians would say that the Tuareg (who are related to the Berber of North Africa) think they’re better than them by virtue of their lighter skin. I know that when I lived there I was told several times by Tuaregs that they were like me, eg. white and that “we” were not like those “black people”. Sadly, the misunderstandings and stereotypes go both ways and are part of the undercurrents playing a part in where things stand today.

Mutiny in the capital and rebellion in the north

After the fall of Ghaddafi, a mass of Tuareg fighters migrated back to the Sahara region of Mali armed with weapons and ammunition. They rekindled the rebellion and are well-organized and well-armed. When they began attacking small settlements in the far north, the Malian army found itself under-equipped and outgunned. The Malian army suffered many defeats, and the President Amadou Toumani Toure (ATT) was accused of being “too soft” on the rebellion and of not giving the army the resources they need (food, manpower, ammunition).

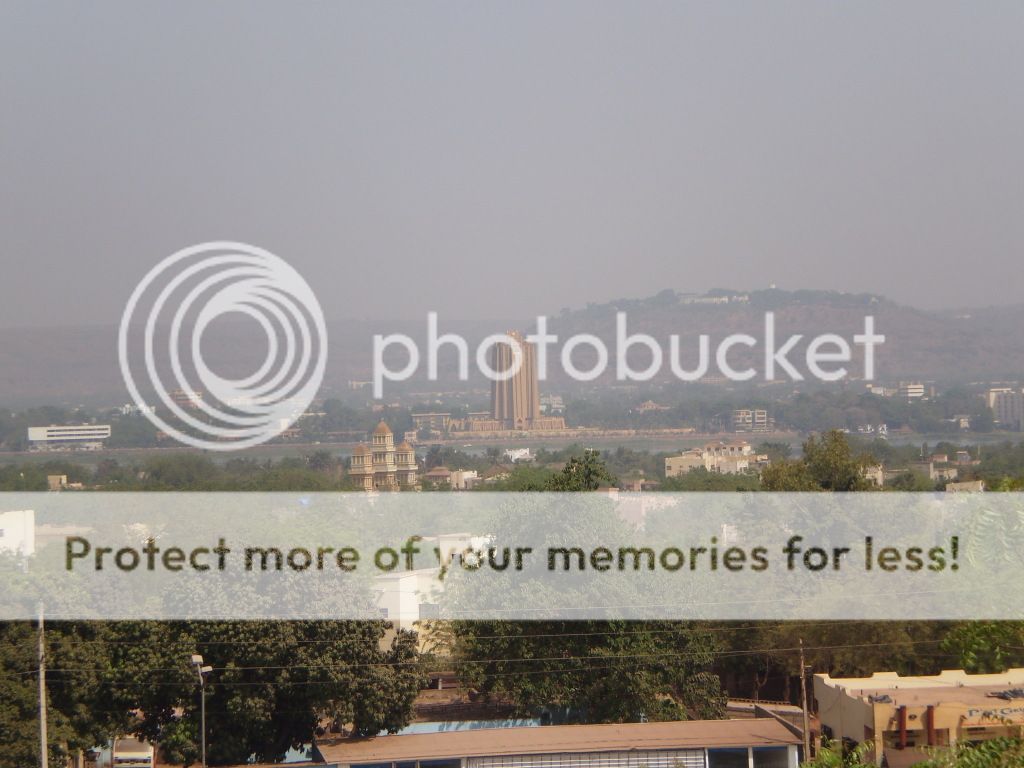

On March 21, a visit from the defense minister to the troops garrisoned outside the capital of Bamako turned into a confrontation with angry soldiers protesting what they saw as incompetent leadership. This escalated into a mutiny and the soldiers stormed the presidential palace as well as the offices of the national television station. This junta of mid-level officers led by Captain Sanogo suspended the Constitution, saying that they would return the government to a democratically elected transition. Ironically, elections were due to be held in less than a month, and President ATT had made clear his intentions to step down and retire.

In the midst of this confusion in the capital, Tuareg rebel groups in the north took advantage to consolidate their positions and advance to capture more territory. Within three days time, they had captured the regional capitals of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu and declared that they were “liberating” the country of Azawad.There are at least three distinct groups involved in the fighting as well as opportunistic criminal and bandit elements. Here is a brief (and overly simplistic) rundown. The MNLA is a collection of liberation-minded Tuareg groups who are seeking independence or at least more autonomy from Mali. Ansar Dine is another group whose goal is not Tuareg independence but the imposition of Islamic law in Mali. Finally, there is AQIM or Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb which is associated with factions in Algeria and who make money from drug trafficking across the hostile desert terrain and kidnapping hostages for ransom. Reports indicate that the takeovers of Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu have been achieved by some or all of these groups working together. What remains to be seen is whether or not they will turn on one another now that their territorial objectives have been achieved. Reports from Timbuktu and Gao seem to indicate that in fact the Islamist elements have the upper hand.

In the meantime, ECOWAS (the economic community of West African states) held emergency meetings to respond to the coup. ECOWAS took a very hard line with the junta, no tolerance for coups. They gave them 72 hours to return the country to constitutional rule. Sanogo announced a return to the original constitution (he and his mutineers had hastily drawn up a new constitution in the span of about a day), but refused to step down or to agree to a timeline for transition. ECOWAS instituted an embargo, closing the borders with Mali and freezing their ability to draw on the common West African currency, the CFA. Within the span of a few days, a deal was negotiated in which in which the speaker of Mali’s National Assembly, Dioncounda Traore, was sworn in as interim president. He has 40 days to organize elections. The most pressing issue is resolving the crisis in the north.Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world. The land in which most of the population lives is increasingly affected by desertification and the effects of global climate change. Already this year was forecast to be a bad one in terms of drought and food insecurity. The precarious security situation in the north has displaced thousands already and more will likely follow.

The Mosaic of Mali

Almost all of the major ethnic groups in Mali have had their heros and their time of ascendancy. Bambara, Songhai, Soninke, Fulani, Mande, each can point to a time in the history and cite how their ancestors were great and made a real contribution to the shared patrimony of Mali. There is a fascinating practice that goes on to this day called “le cousinage” or “sanankuya” which in English is roughly translated as “joking cousins”. During my Peace Corps training, this was one of the first bits of culture that we learned and started to practice along with our budding language skills. Essentially each last name, ethnic group and/or caste is related to certain others as “joking cousins.” When you meet someone, perhaps sit beside them on the bus, buy something from them in the market, etc. one of the first questions asked will be “what’s your family name”. If it turns out that you and your interlocutor are joking cousins, you immediately begin trading good-natured insults and jokes. You’re no longer strangers; the ice is broken. We were told by our Malian trainers that they credited the long history of peace and diversity to this practice. By disarming potential rivalries through humor and giving a social outlet for acknowledging shared cultural history, serious fighting or feuds could be avoided.There are infinitely more small quirks like this this that one could share to demonstrate the Malian propensity towards dialogue, tolerance and optimism. I could tell you about the amazing musicians, known around the world for their artistry, talent, and ability to synthesize musical traditions across ethnic lines, or about the griots, oral historians who to this day can recount the entire histories of the clans to which they are traditionally linked, or the culturally ingrained practice of using mediators to smooth over disagreements in the community, or the traditional greetings and blessings that complete strangers exchange every day, or the way that passerbys are invited to share meals. I wish I could find the words to show clearly the Mali that I know and love and the degree to which this recent violence is so contrary to the norm.

The Malian people are generous and community minded. From the empire of Mali thousands of years ago to today, their culture and identity has remained intact. One can only hope that the values of dialogue and jiatigiya (hospitality) will see them through these dark days.

I hope that this diary has given at least a small glimpse at a situation that affects a country that is near and dear to my heart. I would be happy to take a stab at any questions or engage in discussion with anyone who is interested or curious.

For further reading, I’d recommend the following:

Bridges from Bamako – an excellent blog that has great analysis before and throughout the coup

Disaster looms for people of Mali as country is split by revolt

Hungry for Democracy – The Malian peasantry and the coup

The coup in Mali is only the beginning

Musical reflections on dramatic events in Northern Mali

Finally, I leave you with one of Mali’s most famous exports, music. Here we have artists from many of the major ethnic groups (including Tuareg) united in song and in celebration of their shared culture.

I can’t hit submit without forgetting to thank everyone at Black Kos for being so supportive, Denise Oliver Velez for encouraging me to take a stab at diarying this story, nomandates for getting me plugged into the New Diarists help network, and bent liberal for LOTS of editorial advice and patience. Aw ni ce, aw ni baara ji. Thank you!!